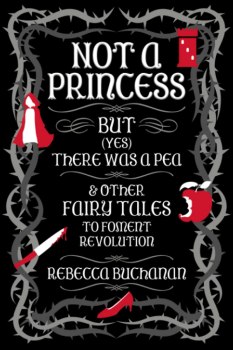

Not a Princess, but (Yes) There was a Pea, and Other Fairy Tales to Foment Revolution by Rebecca Buchanan

Not a Princess, but (Yes) There was a Pea, and Other Fairy Tales to Foment Revolution by Rebecca Buchanan

Jackanapes Press (September 2022)

170 pages; $15.99 paperback

Reviewed by Joshua Gage

Rebecca Buchanan is the editor of the Pagan literary ezine Eternal Haunted Summer, and is also a regular contributor to ev0ke: witchcraft*paganism*lifestyle. She is also the editor-in-chief of Bibliotheca Alexandrina, the publishing arm of Neos Alexandria. Her newest collection of fairy tale poems is Not a Princess, but (Yes) There was a Pea, and Other Fairy Tales to Foment Revolution.

Fairy tale poems and fairy tale retellings are nothing new. There are multiple anthologies, book series, and even literary journals dedicated to the subject. So it takes a skilled author to rewrite the tales in such a way as to make them fresh or new for the readers. Buchanan is certainly up to the task, and her retellings are striking and dark. Often told via persona poems, the poems in this volume ask interesting questions about the fairy tale characters and their perspectives. For example, a poem like “As the Mirror Sees It,” takes on the question of what the Magic Mirror saw when looking at the Evil Queen. The poem begins:

Day by day,

she sits before my glass,

doubt and jealousy

poisoning her heart.

While we know the queen is evil, it’s interesting to see this from the mirror’s perspective, and provides readers with a voice rarely heard from the tale. Elsewhere, Buchanan uses a narrative voice to provide readers with alternate versions of the stories. This revisiting and rewriting of the tale provides a psychological perspective for the reader into the minds of characters who are often ignored, and also asks the readers to consider, for a moment, what would happen if the magic and fantasy were taken out of the tales, and these were real people with real problems using the fantastic as an escape or excuse. For example, “The Daughters of the King” begins:

They sit in a circle, patient in

their plotting and their planning, ripping

their shoes to shreds with fingernails

and teeth.

In this poem, the twelve dancing princesses are not fleeing their bedroom to escape and dance, but they are fleeing, and the truth of the tale is much darker.

Elsewhere, Buchanan uses experimental forms and approaches to these poems, presenting modern interpretations on classic tales. For example, “Enchanted Forest News” presents a radio or television newscaster presenting a news program, using various tales and character quotes to critique various news outlets and political approaches to social problems in a biting critique of contemporary society. This is a fun approach to fairy tales, and one that’s been done before, but that Buchanan certainly makes her own. These poems also serve as lighter fare against the darker and harsher realities of the other verse, and help the reader navigate through the emotional turmoil of the collection.

Overall, this is an interesting collection. Buchanan has taken classic fairy tales and reworked them into narrative and persona poems that retell or reimagine the stories, often making them darker and more horrific. Buchanan’s poems stand out with their unique plots and psychological reinterpretations, so while this is not a unique take on fantasy or fairy tale poetry, it is a collection that readers will want to own and reread. Fans of horror poetry and dark fantasy or fairy tales will thoroughly enjoy this collection.