I remember my first Robert Aickman story vividly. It was in February. Early in the morning. As the snow fell outside on an already white winter morning, I sat very still in my favorite chair, reading “The School Friend,” and wondering…just what was I reading? A story about a long-lost friend returning after her father’s death, to comfort her old school friend, who had fallen into a lonely life? Or was this friend something…more?

Or was she less?

Why did she initially look the way she had in school twenty years before? Youthful, unchanged, almost—as protagonist Mel thinks—virginal. Why so pale white after living in such sunny climes, when she should be tanned? Why did it seem so disturbing that she’d moved into her deceased father’s house, all alone? And why did she seem to decline so quickly in dress and manner after moving into her dead father’s house?

What was she?

To this day, I’m still not exactly sure. However, I’ve come to believe that’s the ultimate delight in experiencing Robert Aickman’s work. He wrote stories which took place on a nebulous borderland between the pedestrian and the strange; the mundane and the surreal. After reading Aickman, everything feels off kilter and uncertain. You can tell very easily where the story began—that’s one his greatest strengths, how he roots his stories in realism—but you’re never quite sure where he left you, or what to make of where he left you.

For example, what happens at the end of “Bind Your Hair”? Does Clarinda really see people transform into animals under the moonlight? Or does she merely observe from afar an elaborate pagan rite celebrating nature and people trying to get into touch with their “animal selves?” Set against the backdrop of a city girl being told by her in-laws that she simply isn’t “ready” to discover her “true” nature.

In “The Waiting Room,” Edward Pendlebury misses his railway connection and has to spend the night in a small town with no lodgings. A rather gruff porter says he can sleep in the station’s waiting room. That night, Pendlebury dreams the room is filled with kindly people of different dress and from different stations of life, and though he can tell there’s something odd about them…he doesn’t quite know what it is.

In “The Waiting Room,” Edward Pendlebury misses his railway connection and has to spend the night in a small town with no lodgings. A rather gruff porter says he can sleep in the station’s waiting room. That night, Pendlebury dreams the room is filled with kindly people of different dress and from different stations of life, and though he can tell there’s something odd about them…he doesn’t quite know what it is.

The next day, another porter informs him that he never should’ve been put in that waiting room to spend the night. Didn’t he know that the whole station was built on the site of a jail? And that the waiting room itself centered over its burial ground?

Did Pendlebury dream of a room filled with people? Or did something else happen? Why does the porter suggest that Pendlebury will never be the same after his experience? These questions and more are what lingers after reading one of Aickman’s “strange stories.”

*

Of the late Robert Aickman, bestselling author and horror legend Peter Straub says:

From the first I understood that he was a deeply original artist. This in no way implies that I understood Aickman immediately because I didn’t. Sometimes I would look up at the end of a story, feeling that the whole thing had just twisted itself inside out and turned into smoke—I had blinked, and missed it all. It took me a little while to learn to accept this experience as valuable in itself and to begin to see how the real oddness of most of Aickman’s work is directly related to its psychological, even psychoanalytic, acuity.

Unconscious forces move the stories itself, as well as the characters, and what initially looks like a distressing randomness of detail and event is its opposite—everything is necessary, everything is logical, but not at all in a linear way. To pull off this kind of dream-like associativeness, to pack it with the menace that results from a narrative deconstruction of the notion of”ordinary reality,” to demonstrate again and again in excellent prose (no dumb experimentation or affectation here) that our lives are literally shaped by what we do not understand about ourselves, requires a talent that yokes together an uncommon literary sensitivity with a lush, almost tropical inventiveness.”

What I’ve always loved about Aickman’s stories is the slide from the mundane into the surreal is so gradual, if you’re not paying attention, you’ll miss it. He preferred to call his stories “strange” instead of “horror,” and in my mind, that fits perfectly. His stories are constructed on a solid foundation of realism, which is essential, because what is familiar is slowly, carefully twisted out of proportion.

This realism lulls the reader to sleep, convincing them they’re reading about an utterly mundane world. Then, something odd happens. Something which keeps coming up. Which certainly looks “odd,” but you imagine there’s an explanation for it somewhere. However, as you keep reading, Aickman’s realism continues to rope you in. Even after we’ve been presented with a possible explanation for the weirdness, Aickman is content to leave us there, dangling, wondering exactly what happened.

In his story “The Unsettled Dust,” the manor at Clamber Court is perpetually clogged with dust. Is it because of the dusty roads and the wind? Or because of the “accidental” roadway death of one of the Clamber sister’s betrothed, at the hand of her possibly jealous sister? This is never made clear.

Neither is the true nature of the Russian family celebrating in an old, abandoned house in “The House of the Russians.” In this tale, a land surveyor walks a piece of property on Finland, because a large land-holder wishes to purchase it. At night, he comes across a series of abandoned houses which seem to be hosting joyous family celebrations. In one, he encounters a young boy who can’t speak English, but who insists on giving him a coin. When he visits the same house on another night—after learning they once belonged to Russians who threw extravagant parties, but were eventually forced out because of political disfavor—he finds an abandoned house so blood-stained he can see outlines of bodies on the floor. A ghost story, perhaps…but whether or not the man met ghosts or itinerant Russians is never made clear.

In “The Next Glade” Noella, a young mother and wife, entertains thoughts of possibly taking a lover while her husband Melvin is working out of town. A man she met at one of her friend’s parties (or so she believes, because she can’t quite remember) named John Morley-Wingfield (or so he says) comes calling on her house, to go for a “walk in the woods.” In a scene fraught with repressed sexual tension and things unsaid, she welcomes him to her home with milk and tea. After, they finally take their walk through the woods behind her home. He praises her beauty, and she allows him to put a gentlemanly arm around her waist. After a few minutes, however, the man excuses himself to “explore for a little bit” over in the next glade. She takes it as the perpetual “call of nature” to relieve himself, something her husband is prone to, also.

In “The Next Glade” Noella, a young mother and wife, entertains thoughts of possibly taking a lover while her husband Melvin is working out of town. A man she met at one of her friend’s parties (or so she believes, because she can’t quite remember) named John Morley-Wingfield (or so he says) comes calling on her house, to go for a “walk in the woods.” In a scene fraught with repressed sexual tension and things unsaid, she welcomes him to her home with milk and tea. After, they finally take their walk through the woods behind her home. He praises her beauty, and she allows him to put a gentlemanly arm around her waist. After a few minutes, however, the man excuses himself to “explore for a little bit” over in the next glade. She takes it as the perpetual “call of nature” to relieve himself, something her husband is prone to, also.

The man never returns. As time passes, Noelle becomes more nervous. Finally, she calls out that she must leave, because her children are expected home soon. She takes her leave, and when she returns home she calls her friend Mut, who threw the party to begin with. Mut claims not to know whom Noelle is speaking of. According to her, no man by that name attended her party, though she can’t say for sure.

Noella hears nothing more from Mut for several months, nor does John come to her door again. She, for her part, stops walking in the woods altogether, until one Sunday her husband Melvin suggests a walk in the woods with the children. Despite Noelle’s half-hearted protests they proceed, and the entire time she dreads coming near the glade where John disappeared. Even as Melvin contrives to send the children off playing a game and he tries to steal some private time with his wife, Noelle wonders—though she knows it’s impossible—if the man who might’ve been her lover is still in the woods somewhere.

In attempting to woo his wife for a quick romantic tussle in the woods, Melvin finds the glade, and suggests they go through. Noelle goes first, and what she finds is also impossible: a small timbered house in the middle of the clearing, with John Morley-Wingfield digging in one of the garden beds. Though she wishes to flee, she can’t, struck dumb by the sight, as John looks up at her in confused horror. Noelle turns and runs, and finds her husband’s hand cuts badly by thorns, streaming with blood. He eventually contracts some sort of baffling blood disease and dies a slow, withering death.

After the funeral, Noelle’s would-be lover comes to her, expressing her sorrow and regret at her loss, also insinuating he could offer even more in the way of support. Noelle doesn’t necessarily rebuff his advances, knowing she and her children are in rough straits, facing an uncertain future, but she insists on knowing why John didn’t tell her he lived so close. He denies having a home in the glade, or doing any gardening. She insists she saw him there, before a small house, and he challenges her to take him there. She accepts, and leads him into the woods, where they’d walked five months earlier.

As they’re pushing through the woods, she keeps retelling her story, and he bemusedly keeps denying it. When she’s about to push through into the glade, she asks if everything is all right—he’s been lagging behind her—and he offers her an odd response: “Go on as though I were not there.” Noelle takes a moment to think about it—which also seems strange—and then pushes through.

This entire time she’s heard strange sounds from where she believes the house to be. A tapping, hammering, clanging. When she finally pushes through the glade she finds not a house but a factory. There is something of a garden left there, but it is now withered and unkempt.

Of John Morley-Wingfield, there is nothing. At the end of the story, Noelle speaks with a close friend, wondering if she’s ever taken a lover herself (she has) and whether that means she doesn’t love her husband (no, it doesn’t, she still loves him). She then inquires if her friend ever had neighbor by John’s name, and her friend says no, she never heard of him, and says Noelle “just dreamed him up.”

So was it a ghost? A figment of Noelle’s imagination, of her repressed desire to have an affair? At the end of the story, her son Agnew asks about John. Apparently he saw Noelle walking with him, asking if Noelle is planning on marrying him. Noelle says no, the man was only “Daddy’s friend.” When her son persists, asking why she was walking for him, she says, “He wanted to take me out of myself. It was kind of him.”

So was it a ghost? A figment of Noelle’s imagination, of her repressed desire to have an affair? At the end of the story, her son Agnew asks about John. Apparently he saw Noelle walking with him, asking if Noelle is planning on marrying him. Noelle says no, the man was only “Daddy’s friend.” When her son persists, asking why she was walking for him, she says, “He wanted to take me out of myself. It was kind of him.”

A ghost? A spirit? Something conjured by Noelle herself, to help her cope with her repressed feelings? There is no clear answer, though the story offers a kind of closure, regardless.

*

In “No Stronger than a Flower” a newlywed seeks advice about how to best change her appearance for her new husband Curtis, who has been subtly hinting at changes he’d like to see. Nesta writes to a woman (possibly of ill-repute) and then meets with her regarding this. Whatever exact advice Nesta receives (we never quite find out), it hasn’t necessarily been in how to make herself more attractive to Curtis. Whatever Nesta learns, it’s that men don’t really want change, despite their insinuations to the contrary.

Setting out to prove this, Nesta slowly changes her appearance over a period of time—dressing more extravagantly, and filing newly lacquered nails to razor points—slowly driving Curtis to distraction, almost enraging him, simply because she wasn’t the woman he married. The interesting thing is, despite all the outward changes—the sharpened nails, the changes in dress and behavior—Curtis is unable to pinpoint exactly what about his wife has changed. This maddens him even more.

Even so, Nesta continues, nerves growing stronger, even as her husband weakens before her. Toward the end, she begins wearing a veil at all times. This produces a profound effect on Curtis. Because he can only see her lips, he entertains a mad, consuming desire to kiss her, at the same time repulsed by the reaction his transformed wife has created in him.

At their final dinner together, Curtis makes one final entreaty, saying he wishes things could go back to the way they were. She unwinds her veil, so he can have one final look…but despite the fact she’s wearing elaborate makeup, he still can’t put his finger on what has changed in her. She blows the candles out, kisses the back of his neck, leaving him alone in the dark, knowing he’ll never see his wife ever again.

This is a great example of an Aickman story in which nothing overtly supernatural has happened (at least, we don’t think so), but the slow working of Nesta’s transformation (which Curtis ironically initiated) works on her husband until he felt as if he could no longer trust his senses. There is no source we can point to for this surreal atmosphere. No haunt, no spell, and we’re not sure what advice Nesta was given. Still, it feels weird. Slippery. Something “strange” has happened; and we’re not sure what it is. All we’re sure of his how unsettled we feel after reading it.”

*

I could spend the next ten pages summarizing every Robert Aickman story I’ve read, and describe the surreal atmosphere inspired by his words. I could praise his meticulous attention to detail, and his precise wording and imagery. I could talk about the smoothness of his prose, and how effortlessly he lulls readers into a sense of complacency and normality. I won’t do that, however, in the hope that you’ll seek out his work for yourself.

As to his impact on me as a writer—though I’ve hardly read everything he wrote, I can honestly say his writing has impacted me almost as much as Charles L. Grant’s has. I simply adore his ethics: beginning a story in an utterly prosaic and mundane world, and then slowly turning it off kilter, sliding the reader into something strange and disturbing.

As to his impact on me as a writer—though I’ve hardly read everything he wrote, I can honestly say his writing has impacted me almost as much as Charles L. Grant’s has. I simply adore his ethics: beginning a story in an utterly prosaic and mundane world, and then slowly turning it off kilter, sliding the reader into something strange and disturbing.

This is something which has become my starting point for every short story. I don’t set out to write “horror” or something “weird” or “scary.” I find a starting point which occurs in a world which I hope is realistically rendered and detailed. Then—following whatever emotional flaw or need or nightmare my protagonists have—I watch it slowly develop into something strange, surreal, and on the edge of horror. “Horror-ish,” if you will. That’s the best way to describe the bulk of my work, and, for better or worse, in large part I have Robert Aickman to thank for that.

Robert Aickman’s Fiction:

Cold Hand in Mine

The Wine Dark Sea

The Unsettled Dust

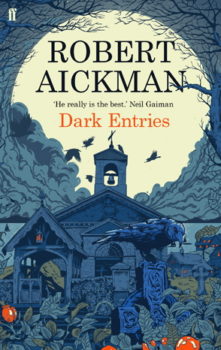

Dark Entries

The Late Breakfasters and Other Strange Stories

Compulsory Games

The Inner Room

Painted Devils

Kevin Lucia is the Reviews Editor for Cemetery Dance. His short fiction has appeared in several anthologies. His first short story collection, Things Slip Through, was published November 2013, and his most recent short story collection, Things You Need, was released September, 2018. He’s currently working on his first novel. For free monthly fiction, book reviews, YouTube commentaries, and three free ebooks, visit www.kevinlucia.blogspot.com and sign up for his monthly email newsletter.

I have always loved his writing ??.